Submarine Channel

Best Dystopian Movies based on Literature

Top5's

Best Dystopian Movies based on Literature

Visions of a bright future where technology has liberated humankind from the hardships of labor and everybody’s free to pursue their dreams and goals. Bright images of fuzzy, multi-colored fluffy things. Scenarios where world leaders act responsibly, always prioritizing the common good. Postcards of beautiful people laughing without a care in the world, with a bright sun on the horizon. Sorry, you won’t find any of that here.

By Benjamin Pineros

Since the dawn of time, humanity has always tried to build a paradise on Earth. From the construction of the very first wheel to the invention of the microchip, human ingenuity has raised the possibility of these ideal scenarios becoming a reality. And undoubtedly, we’ve come a long way.

But it feels like for every step we take forward, we take two steps back. The darkest aspects of human nature always come to taint our dreams of progress, impeding that ideal promised land to ever come to fruition.

Kings were replaced by industrial tycoons, more than 2 billion people live in poverty and most of us spend half of our waking life devoted to making money for someone else.

And damn, where’s my flying Delorean?

Purposely or tangentially, artists have always played the role of aesthetic-obsessed historians capable of rendering a distinctive snapshot of the world around them. They document the anxieties of the present and warns us about the dark traps hidden in those promises of a bright future.

In times when Amazon employees have to pee in water bottles in fear of losing their jobs and workers grind their tendons away building iPhones, the genre of dystopia seems as relevant as ever.

As part of the release of the dystopian motion comic Ascent from Akeron, Submarine Channel looks at the best dystopian stories in popular culture.

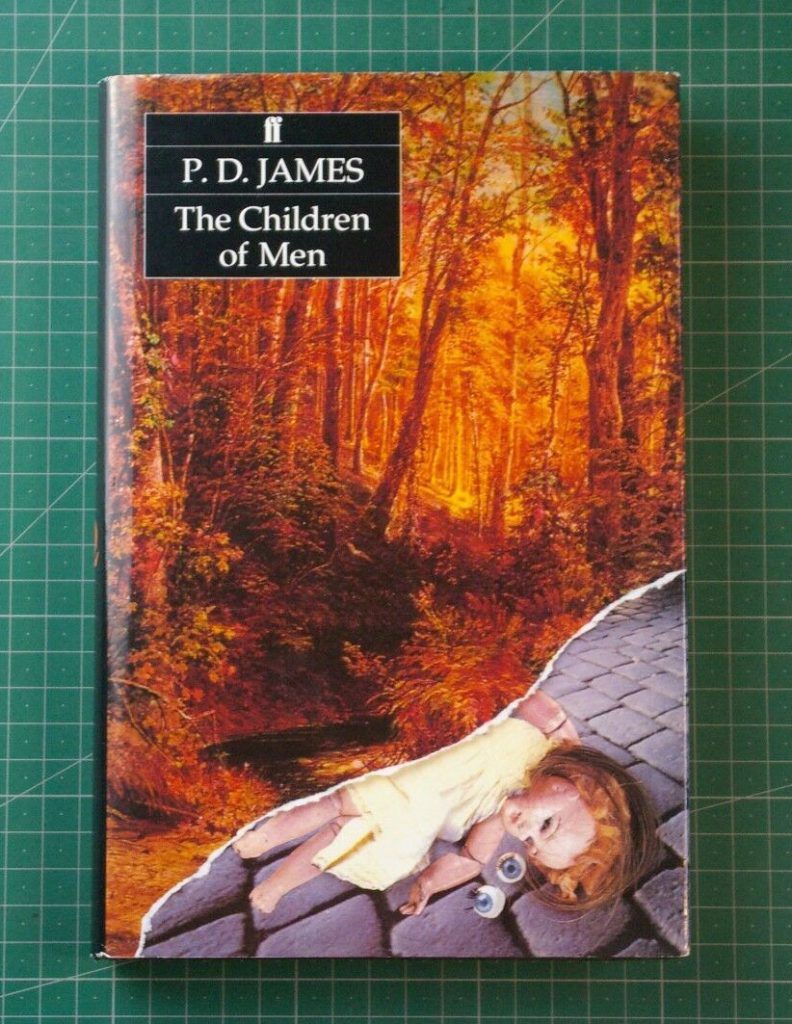

Children of Men (2006)

Global political instability. Refugee crises popping in every continent. World leaders resorting to anti-immigrant rhetoric. All these are real news right now, symptoms of an exploding malaise that has been brewing in the shadows for a couple of decades. “Children of Men” spotted the signs back in the early aughts and created a vision of the near future that today, unfortunately, feels too close to home.

There are segments in this film that we can easily mistake as current day news clips. Set in 2027, two decades of global infertility have left society on the verge of collapse. Massive migrations are spreading all over Europe, paired with terrorist attacks in every capital. To address the overwhelming crisis, the U.K. has veered towards an authoritarian government that has closed the country’s borders and herds its people with a discourse of Nationalism and “security first”.

Sounds familiar?

Theo Faron (Clive Owen) is a minor bureaucrat who hasn’t been able to recover after losing his child to a flu pandemic in 2008. The tragedy has turned him into this broken, cynical alcoholic with very few things to look forward in life. Theo basically is just burning his days away at a dull desk job.

Meanwhile, his ex-wife, Julian (Julianne Moore) has opted to deal with the loss of their child by immersing herself in political activism, becoming the leader of “The Fishes”, a militant human rights group outlawed and hunted by the government.

Everything changes after Julian asks Theo for a favor, on the surface just a minor errand that will eventually prove to be crucial for the survival of the entire human race.

This is a bleak, aging world with an ever-present sense of despair; in “Children of Men”, there’s no hope, no future, and everything is depressing as fuck.

You won’t find here any spectacular shots depicting mammoth cityscapes full of flying cars and cyborgs jaywalking down the streets. And it’s precisely the lack of emphasis on technology, — explicitly choosing not to focus on phones, computers or “The Internet” — that makes this film timeless. This is science fiction that opts to explore the socio-political dynamics of the future instead of showcasing flashy gadgets, and that is why Children of Men is one of those films that just like fine wine — or Converse sneakers — ages very well.

Curiously, underneath all the layers of thoughtful, heady themes, Children of Men is in essence an unorthodox, gripping chase flick. Particularly, there are two crucial moments that Alfonso Cuarón and his partner in crime, cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, chose to portray in long uninterrupted takes that could well rank among the most jaw-dropping action sequences in the history of cinema. And no, I’m not exaggerating. True technical and artistic wonders result of an elaborate choreography, new camera rig technology specifically created for the film, clever editing and a bit of CGI; the long shots in Children of Men don’t have anything to envy those in Welles’ “Touch of Evil” and Tarkovsky’s “The Sacrifice”.

I remember that when I saw the film in the theater for the very first time, I could hear people in the audience gasping and puffing in awe. When you talk about this movie with anyone, chances are those two shots are probably the first thing to come up in the conversation.

Although based on P. D. James’ 1992 novel “The Children of Men”, the movie adaptation strays away ostensibly and purposely from the source material. Director Alfonso Cuarón has famously stated that he didn’t want to read the novel during the screenwriting process; he and writer Timothy J. Sexton threw away most of the book’s plot out of the window and turned the film into a very different beast.

P.D. James’ book focuses on the political intrigue, reflects over the corruption of power, and serves as a lengthy exploration on how the world willingly surrenders to totalitarianism in the face of a crisis. The film, on the other hand, is a much tighter tale of redemption and hope.

Although critics raved about it at the moment of its release, — I recall one mainstream critic so impressed he said it was the best movie of all time, only to retract later after the backlash and media scorn — the movie was a complete commercial failure. Universal chose to release it on Christmas, — probably the worst time of the year to premiere a film about the downfall of civilization — and promoted it with what is possibly the worst trailer in the history of trailers. Like, really, the trailer for Children of Men is absolutely awful.

Costing around $80 million dollars to make, it managed to gross less than $70 million and was painfully shunned at the Oscars, receiving only three nominations for best-adapted screenplay, best cinematography, and best editing, winning none.

Incredibly unsuccessful at the time of its release, Children of Men has slowly become a cult classic, earning the appreciation it deserves and certainly standing as one of the most realistic portrayals of the future ever done in film.

Fahrenheit 451 (1966)

Life is tough already, why make it worse with art?

Novels are cruel inventions devised only to inflate the writer’s ego and make people unhappy. They make us think and feel and bring us the uncertainty of freedom. Books provide fictions that lead society to long for a life that is unattainable, they sell impossible dreams that only result in heartbreak

In the government’s search to cut out all of that which brings unrest, firefighters are not assigned to put out fires, but to start them. Their sole responsibility is to burn books out of existence, and if necessary, burn the readers with them.

As over-the-top and ludicrous as this oppressive future might sound at first, the world described in Fahrenheit 451 is a throwback to real dark periods in human history where books have been thrown into bonfires and art has been considered as politically inconvenient.

François Truffaut was introduced to international mainstream audiences just until 1977 when he played French scientist Claude Lacombe in Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, but at that point, he’d already earned himself a place among one of the most important directors of all time.

Since his debut in 1959 with “The 400 Blows”, Truffaut spearheaded what is known as “La Nouvelle Vague”, a French movement that lasted almost two decades and produced some of the most influential titles in the history of cinema. The introduction of improvised dialogue and naturalistic acting, jump cuts, non-linear narratives, long tracking shots and a preference to shoot on location, revolutionized the world of filmmaking in its time and permeates the works of everyone from Francis Ford Coppola to Spike Jonze.

In the mid 60’s Truffaut was one of the sensations of the European scene, with all of his three films to that point being lauded by critics and having enjoyed very successful runs in the festival circuit. In 1966, he was entrusted to his first big-budget project, the British produced adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s sci-fi classic Fahrenheit 451 from 1953.

It was the first time Truffaut shot outside France, his first time handling a cast of international stars, his first color film and his first time dealing with the pressures that come with big budget filmmaking.

A troubled production with a mixed reception in its day, the film turned out to be the oddest entry in Truffaut’s filmography. It’s a movie that despite displaying most of his stylistic traits doesn’t quite feel like the rest of his body of work.

In comparison, Fahrenheit 451 feels stiff and lacks the freshness of Truffaut’s other movies, but in a sense, it’s his most far-reaching and universal work.

Amidst a world where people are numbed by mindless escapist entertainment via TV shows and drugs, — cough, cough — the story follows Guy Montag, a dedicated firefighter who starts to feel interested in the books he burns. After meeting a neighbor that slowly introduces him to a different worldview, this once loyal enforcer of the ideals of the government begins to question his job, his life, and his marriage.

Contrary to HBO’s terrible adaptation from 2018, Truffaut’s version is very faithful to Bradbury’s novel. Some events are compressed and slightly changed, and an important character is omitted, but overall the screenplay respects the central premise and plot structure of Bradbury’s groundbreaking novel.

Truffaut understands the nerve of the book so well, the film even starts with a narrator reciting the credits instead of rendering them on screen, in an allusion to a culture that doesn’t know how to read anymore.

The novel serves as a commentary on how new forms of mass media can degrade our culture, reduce our attention span, and kill society’s interest in literature. Truffaut’s version, on the other hand, is a critique on bureaucracy, totalitarianism, and the 50s family lifestyle. But both share the same objective, to bring into the spotlight the dangers of censorship.

Fahrenheit 451 is more than fifty years old already, and you could think that the menace of government censorship was defeated with the arrival of the Internet, where the flow of information is so vast no institution could ever control it.

But sadly, it’s a dirty move governments of today still have in their playbook.

The Trump administration has taken a proactive stance to tone down or eliminate completely the threat of climate change in EPA’s documentation, editing out as far as they can stretch it words like “greenhouse gases”, “fossil fuels” and “global warming”.

Meanwhile, China has set in place what is known as “The Great Firewall of China”, a monstrous apparatus of control that allows authorities to monitor the online activity of individuals and block any content they deem as inappropriate.

Do you know that almost 200 journalists — that’s enough people to fill a Boeing 727 — have been killed in Colombia since the 1980s because their reporting was deemed as “inconvenient”? Or that pornography featuring female ejaculation is censored in the UK?

Unfortunately, in a world where science and art are still being declared as political adversaries, saying the truth can cost your life, and government boards decide what kind of porn you should watch, the message of Fahrenheit 451 continues to be frighteningly relevant.

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Juvenile delinquency, brutal beatings, corruption, murder, pederasty and gang rape. It’s difficult to think of another movie that has depicted such a long list of heinous acts, and even harder to find one that had managed to stylize these grotesque expressions of violence to the point of turning them into artistic abstraction.

Yeah, prepare yourselves my little droogies, this trip to the filmdrome will be a real horrorshow.

Set in a cold, gray and gloomy dystopian version of Britain in the near future, the story follows the exploits of a charismatic teen called Alex DeLarge. He lives with his parents, goes to school and on the surface, appears to have the normal life of any adolescent. But in reality, Alex is the leader of a dangerous small gang of thugs that terrorizes the city every night in a deranged, criminal frenzy.

Alex is a witty, sophisticated teenager in love with Beethoven’s music, who exhibits a complete detachment to everything and everyone. Lacking any sense of empathy, compassion or responsibility, he’s capable of the most gruesome and depraved acts you can possibly imagine of. Even more frightening, he perpetrates these horrific crimes with the naiveté of a little child who pulls the wings from a butterfly out of boredom. It’s this absolute desensitization that makes of Alex probably one of the most frightening villains in the history of cinema.

True back in 1971 and valid still today, general audiences have become less and less responsive to violence on screen. It seldom produces any deep emotional impact because we are accustomed to seeing it everywhere.

But A Clockwork Orange works your brain differently. In time you can sure lose some of the plot details and whatnot, but no matter how many years pass, you will never forget the film’s most brutal scenes.

The images are so shocking not because the movie is particularly graphic or gory, but because of the film’s meticulous aestheticization of violence.

Dramatic, well-timed zooms, slow motion, impeccable symmetrical compositions, fluid Steadicam shots; all the traits that make of Kubrick one of the most distinctive directors of all time are in full display.

But it’s not “just” it’s formal exuberance what makes it so enduring. Underneath its heavy stylization lays an irreverent satire with multiple layers of political and social commentary.

On one hand, it’s a blunt critique of all notion of authority; a systematic takedown of family, church, and state.

On another, it’s a warning over how technology — and psychological conditioning specifically — can be used by totalitarian governments to strip people from their free will and exert social control.

It might sound crazy, but that concern is actually very real. Since the apparition of Behaviorism during the 1930s, many governments and private institutions have been rubbing their hands over the very wicked possibility of being able to effectively condition an individual’s actions.

Just to name one example, the CIA ran between 1953 and the late 70s the very illegal Project MKUltra, a secret program that experimented on human subjects with the intention of developing drugs that allowed mind control.

The 1970s sounds too far for you? Ok, let us revise a little happening much closer to home.

In 2012, Facebook manipulated the feeds of nearly 700,000 users without their consent, in an experiment directed to affect their emotions. Yup. Over the course of one week, Zuckerberg and Co. hid “a small percentage” of emotional words from people’s news feeds to test how that would affect on statuses and the number of “Likes” that people give out.

In a Clockwork Orange, Alex’s crime spree ultimately gets him captured by the government and he becomes the subject of a brutal behavioral experiment — not that dissimilar in principle to those of the CIA and Facebook — to change his personality.

The original novel by Anthony Burgess from 1962 was ultimately a tale of redemption. Alex ends up outgrowing his violent impulses and pursuing a peaceful life as a normal “productive” member of society. This ending was omitted from all American editions of the book prior to 1986 because publishers in the U.S. thought it was not a credible evolution of the character.

Although Kubrick respects the general plot structure of the book, he also decided to omit this redeeming finale, picking a dark, much more cynical end to wrap up Alex’s character arch.

Incredibly divisive from its release, A Clockwork Orange was either lauded as a masterpiece or derided for being nothing more than pornography. Blamed for a short wave of teen crime in Britain in the early 70s, censored by the government and disowned by Burgess himself, time has been kind to the movie, with academics, artists and critics referencing it again and again as one of the most influential films ever made.

It has become such an icon you can see it referenced everywhere today in popular culture, from frequent apparitions in The Simpsons to nods in Rihanna’s “You Da One” music video.

1984 (1984)

“There is truth and there is untruth. Freedom is the freedom to say two plus two equals four. If that is granted, all else follows.”

I work as a journalist and a big part of my job is to have my eyes on the newswires all the time. And I kid you not when I say, I’m reminded of 1984 every single day. The parallels between Orwell’s vision of the future and our current times is nothing short of astonishing, and needless to say, incredibly frightening.

Both the novel and the faithful film adaptation from Michael Radford (Il Postino, The Merchant of Venice) centers around Winston Smith, a low-ranking civil servant who works in a tiny office cubicle at the Ministry of Truth.

The world has suffered a series of catastrophic grand scale military conflicts that have resulted in a complete geopolitical re-organization of the globe. This new world is now composed of three totalitarian superstates — Oceania, Eurasia, and Eastasia — that seem to be engaged in perpetual war against each other.

Winston lives in Oceania, — integrated by the Americas, Australasia, the British Isles, Polynesia and Southern Africa — a territory ruled by The English Socialist Party, known as “Ingsoc”.

A combination of the worse elements from Nazism and Communism, the Party rules society with a very strong hierarchical structure based on fear in which total submission is demanded under threat of being tortured, or “disappeared”.

Although most of the population lives in precarious conditions, a big part of the state-run news is dedicated to constantly repeating record-breaking statistics of economic growth.

The Party is led by “Big Brother”, a fifty-something year old man with a stern appearance that attracts an extreme cult of personality.

Big Brother is omnipresent in society. Cities are ridden with posters with his image, he addresses the citizens in a daily telecast, and all round he’s revered almost as a god.

Propaganda constantly reminds people that Big Brother is always watching every move, his vigilant eyes looking for those who incur in what is called “thought crime”, the illegal act of having unfavorable opinions towards the Party… in your mind.

To capture “thought criminals” the government has instituted the “Thought Police”, a secret enforcement agency tasked with spotting and punishing these unspoken infractions.

Telescreens are ubiquitous in this dark dystopia and play a significant part in surveilling the population. It’s through these home appliances that authorities monitor people’s facial expressions and general behavior to detect their level of loyalty to the Party.

In their pursuit to control every aspect of society, the Party even went to redesign language, creating a simplified version of English called “Newspeak”. For Ingsoc, language is a political weapon, a tool to limit self-expression, personal identity, and ultimately, free will. How can you ever start a revolution if the word “dissent” doesn’t exist in the dictionary?

In Oceania, reality is whatever the Party wants it to be. They continually revise history, changing events, dates, and names to steer the narrative at convenience. “Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past” says one of Ingsoc’s slogans.

Newspeak also incorporates the ultimate instrument to control the masses, the concept of “doublethink”; the possibility of an idea to hold two contradictory beliefs simultaneously, both of them being “true”.

Distorting the very fabric of language makes of reality a malleable concept, allowing Big Brother the ultimate level of control, to fuck with people’s minds.

If you can make people believe in lies or disregard the truth at will, it’s only then that you have achieved complete control. “Doublethink” allows the Party to spout deliberate falsehoods as truths only to pick up the facts again when it becomes convenient. It practically allows them to do anything.

“Doublethink” is prominent in the Party’s toolbox, one notorious example the way they named their ministries. Each name is the exact opposite of their true functions. The Ministry of Truth deals with fabricating lies, the Ministry of Peace is in charge of warfare, the Ministry of Plenty is in charge of overseeing food rationing and the Ministry of Love is dedicated to processing and torturing those captured by the “Thought Police”.

Winston’s job in the Ministry of Truth is to review news clips and historical records and tweak them to conform to Ingsoc’s ever-shifting version of history. While he is diligent at his job, he has reservations about the Party’s methods and writes his feelings in a secret diary.

In this bleak world, sex is only reserved for procreation, but Winston gets involved in a torrid affair with a fellow party worker called Julia, a relationship that exacerbates his subversive ideas and loathing towards the Party.

The somber world that Orwell created for his novel was mainly molded after the modus operandi of the Nazi and Communist Parties of the time. The novel was not devised as a realistic or prophetic imagining of the future, but as a warning based on Orwell’s concerns over the rise of Nationalism, censorship and the advancement of technology.

Ironically, what was originally written as a cautionary tale seems to have been embraced by some as a step-by-step tutorial.

China definitively is one of those countries that has taken Orwell’s vision to heart. Their government has been implementing for decades now what’s probably the biggest state surveillance apparatus in history. There are more than 200 million CCTV cameras across the country, many equipped with facial recognition software. They also have spy drones that look and act like real birds and their police force is being equipped with smart “Terminator” like glasses.

Sum to that their nationwide credit system, which gives each citizen a “social score” that will reward citizens for doing volunteer work or donating blood, and will punish for things like cheating in video games or loitering. In China, if your social score is low, you won’t be eligible for public universities, you will be banned from flights with national carriers, and the government might even freeze your assets.

But it’s not just China. Last year, Taylor Swift’s concert entourage installed stealth cameras with facial recognition in their Rose Bowl gig to capture pictures of her fans and cross-reference them with a database of the pop star’s known stalkers.

Even scarier than all this technology is the rising adoption of the most malicious and destructive instrument in Ingsoc’s arsenal; Doublethink and the manipulation of truth.

Just last April, Brasil’s right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro went on to claim with a straight face that the Nazi Party was a leftist movement, and to make things even more contradictory, he did it just after visiting Israel’s Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial and museum.

Furthermore, Bolsonaro’s Minister of Education is pushing to edit school textbooks to redefine the military coup of 1964 — which lasted 21 years and left more than 400 people disappeared and thousands more tortured, — as a period of “democratic regime by force”

Particularly Orwellian is the political climate in the US now. Trump has made up more than 9000 lies in his first 773 days in office and the president’s advisor, Kellyanne Conway, has famously coined the phrase “alternative facts”.

The Sinclair Broadcast Group, the largest television station operator in the United States by number of stations, was the center of world indignation in April 2018 when Deadspin Video Director Timothy Burke created a clip that exposed how the company enforces its newscasters to read a scripted promo that parrots Trump’s cultural war against the media.

Veteran journalist and former news anchor Dan Rather wrote about the exposé at the time: “News anchors looking into camera and reading a script handed down by a corporate overlord, words meant to obscure the truth not elucidate it, isn’t journalism. It’s propaganda. It’s Orwellian. A slippery slope to how despots wrest power, silence dissent, and oppress the masses.”

1984 is one of those seminal works that has managed to both describe and change the real world at the same time. Most of its concepts, ideas and terminology has embedded into popular culture, making its way into art, film, social sciences and politics. We’ve seen it referenced in all sorts of media, from Apple Commercials to rock albums by Alan Parsons and David Bowie. 1984 is probably the most influential artwork of the XXth century, and to be honest, I wish it wasn’t.

Blade Runner (1982)

What can I say that hasn’t been said already? Blade Runner is probably one of the most studied films of all time, being the topic of countless college courses, essays, documentaries, and books.

Mentioned in practically every critics poll out there, Time Magazine included it in their list of ALL-TIME 100 best films, in 2017 Empire Magazine placed at 13th in their list of “100 Greatest Movies” and IGN ranked it in second place behind Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey in their countdown of the “Top 25 Sci-Fi Movies of All Time”.

If that wasn’t enough, the movie was even named as the best science fiction film ever made by a panel only comprised of scientists organized by The Guardian in 2004.

Despite it being a commercial flop and suffering serious critical backlash at the time of its release, Blade Runner has become an omnipresent cultural icon, inspiring the look and themes of science fiction for the last three decades.

It has also become the film everybody says they’ve watched, but actually haven’t. Yeah, I know you’re smirking right now. How many times have you fallen asleep when trying the hardest to “watch it until the end this time”?

Visually, it’s absolutely stunning and the music is truly mesmerizing, but it lacks the emphasis on traditional narrative and sensible drama that mainstream audiences are accustomed to expect in a blockbuster film.

It was one of the most expensive movies of its time, with a budget of almost $30 million — In comparison, The Empire Strikes Back from 1980 cost $18 million — and was headlined by none other than Harrison Ford, who was probably the biggest name in entertainment at the moment after the successes of Star Wars and Indiana Jones.

Ticket buyers went into the theater expecting an action film full of frantic shootouts, furious explosions, and flying car chases. Instead, they were greeted with an excruciatingly slow-paced, two-hour long exploration of what it means to be human.

Blade Runner is set in the early 21st century, in a time when robots are almost indistinguishable from normal humans.

These synthetic beings — called “Replicants”, but commonly referred to as “skin jobs” — are usually entasked to hard slave labor or are enlisted as soldiers, and have a vital role in the colonization of other planets.

Replicants are declared illegal after a combat team in an off-world colony revolts in a bloody insurrection, leading the Police to form a new special unit called “Blade Runners” to hunt them down.

The story kicks-off after a worn-out cop — Rick Deckard, played by Ford — is assigned to find and execute a small group of fugitive replicants that has escaped to Earth and have hidden in Los Angeles.

Although it borrows elements from the neo-noir comic book from 1975 “The Long Tomorrow” written by Alien scribe Dan O’Bannon and illustrated by Moebius, the film is, in essence, a loose adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s novel from 1968 “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”.

While a lot of details were changed, and the very terms “Blade Runner” and “replicant” are never mentioned in the book, both works take “posthumanism” as one of its core premises; a world in which humankind has gone beyond its biological constraints and is being replaced by synthetic constructs.

The philosophical concept of “brain in a vat” tackled by other subsequent films like “Ghost in the Shell” and “Ex Machina” is explored and taken here to the extreme. Can I be a human even if the only human thing about me are my memories? Can I be “real” if my brain is just a mass-produced assembly of silicon chips and plastic cables?

The world of Blade Runner is one of vast landscapes of towering, dark buildings with massive chimney-like exhausts expelling flamboyant fireballs. It’s the epitome of industrialization gone mad, with glamorous, gigantic neon advertisements reigning above a grim, decaying megalopolis where it never stops raining. This is a world with no green, presented as the ultimate orgy of technology and artificiality, probably as a presage of a future that has lost its soul.

Ironically, the only character in the film to display a glimpse of humanity is the most feared and brutal of replicants — portrayed brilliantly by Rutger Hauer — who delivers at the end of the movie a poetic monologue in what could well be the best single scene in the history of cinema.

Curiously, the movie is set in November 2019. It’s true we don’t have flying cars or off-planet colonies yet, but bioengineering, artificial intelligence, and the rise of mega-corporations are very real elements of today’s society.

Software has already influenced elections. Artificial beings have been found to be infiltrating the cultural discourse on social media. Robots are being victims of discrimination. Google is very close to perfecting an AI capable of talking over the phone and fooling real people. Consumer trends indicate we’re on the verge of a sex bot craze. Private companies are jumping on the race to provide commercial flights to space.

We are just starting to scratch the surface of the ethical dilemmas, philosophical implications and practical challenges these new technologies will introduce to our daily lives. Blade Runner works as a prescient, far-reaching, beautiful exploration of how technology could change the very essence of our species.

If there could be something as “the mother of all films” this might probably be the closest thing to it. So, next time, grab a Red Bull and watch it until the end. I promise you won’t regret it.

Benjamin is a writer, self-taught filmmaker, 3D artist and cook extraordinaire. He has worked in feature animated films, indie video games and is currently a contributor to Australian digital publishing company Conversant Media. In love with all good sounds from Bach to David Bowie, he writes first drafts on paper, hates smartphones and wants to learn to play the guitar someday. For years, Benjamin has worked in his spare time on his personal project “Servicios Públicos” a sci-fi dystopia about tyrant states, overpopulated Latin American cities and some damn awesome robots. Find him on Twitter @iampineros