Submarine Channel

Is Immersive Content the Future of Journalism? III

Is Immersive Content the Future of Journalism? III

Merchandising, merchandising…where the real money from the movie is made! Spaceballs-the T-shirt, Spaceballs-the Coloring Book, Spaceballs-the Lunch box, Spaceballs-the Breakfast Cereal, Spaceballs-the Flame Thrower. [turns it on] The Kids love this one!

Yogurt in Spaceballs, 1987

By Davide Banis

In Part I and Part II of this series, we used the expression “immersive journalism” to identify journalism that employs virtual and augmented reality to add a (literal) layer of depth to its storytelling. After all, as a quick search on Google or its dedicated Wikipedia entry will confirm, this is how the expression is usually intended.

However, I will here argue that this is a limited understanding of what immersive journalism is (or could be) about. In the realm of fiction, where the notion of immersive storytelling is well-established, bulky VR headsets and fancy AR apps have so far failed to meet their pumped up expectations as revolutionary storytelling tools. Indeed, the main driving force behind contemporary storytelling’s immersive turn is world-building – less a tool or a technology than a narrative logic.

What fictional juggernauts such as Star Wars, the Marvel superheroes, and Game of Thrones have in common is that they are first and foremost fictional universes; they are worlds that can be explored rather than linear stories with a beginning and an end. Their endless plots and subplots tell the stories of dozens of characters rather than of a handful of archetypal characters.

Scarily, two out of the three transmedia universes I mentioned are intellectual properties of Disney, the fictional behemoth par excellence. (Credit: FollowingtheNerd.com)

So, yes, what I’m doing here is trying to imagine how the notion of world-building could expand what we mean by the expression “immersive journalism” and whether it could indicate a possible business model for journalism. I’m doing it in three steps.

- First off, I’ll further analyze the notion of immersive storytelling starting from Janet Murray’s book Hamlet on the Holodeck (sort of the Old Testament for immersive storytelling). In particular, I’ll explore the notion of world-building.

- Secondly, I’ll try to imagine how this concept of world-building might be applied to the field of journalism, both at a narrative and at a financial level.

- And finally, I’ll focus on a specific case study. I’ll explore the quasi-fictional universe of a media outlet that over the past few years brilliantly applied the core principles of world-building, Alex Jones’ conspiracy-fuelled website Infowars.

The emergence of immersive storytelling

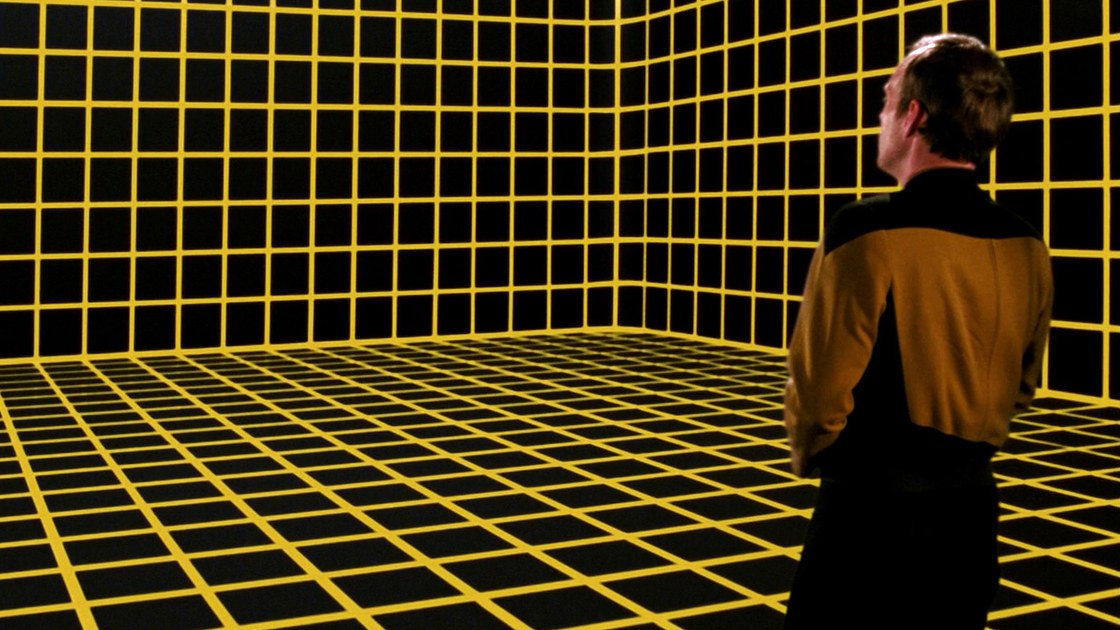

As I mentioned in the first article of this series, in 1997 American professor Janet Murray published the book Hamlet on the Holodeck, where she investigated how computers revolutionized storytelling.

In a nutshell, the author argued that every digital story enjoys four properties: it’s procedural, participatory, encyclopedic, and spatial. The only adjective that probably requires some additional explanation is “procedural”; with it, professor Murray means that every digital story is potentially “made of executable procedures”.

The Holodeck is a concept that Murray borrowed from the TV series Star Trek

To my understanding, it seems that the two adjectives that truly lived up to the test of time are “spatial” and “encyclopedic”. If I think about today’s most successful stories, such as the superhero, sci-fi, and fantasy tales that I mentioned above, they are certainly “spatial” and “encyclopedic”.

What’s more literally spatial than Star Wars’ space universe with its impressively detailed fictional geography of the Galaxy? Or more encyclopedic than Game of Thrones’ intricate story-arcs?

As for the participatory and procedural characters of today’s mainstream stories, it seems to me that they’re expressed less as an interaction with the plot than as the possibility to freely explore the fictional world of the story, just think of recent hits in open-world video games like Spider-man and Red Dead Redemption.

In other words, the participatory affordances of the story are mainly a subset of its “spatiality”.

Red Dead Redemption 2 features the largest map created by Rockstar

In this conception, the most fundamental characteristic of immersive storytelling is that stories become worlds. In his book Convergence Culture (one of the New Testaments of immersive storytelling), media scholar Henry Jenkins reports what an experienced screenwriter told him:

When I first started, you would pitch a story because, without a good story, you didn’t really have a film. Later, once sequels started to take off, you pitched a character because a character could support multiple stories. And now, you pitch a world because a world can support multiple characters and multiple stories across multiple media.

So, the logic of contemporary storytelling is world-building, and while you can certainly build a fictional world in augmented or virtual reality, you can also do without. All you need is a strong concept for a cohesive narrative universe that can spread across multiple media, just think of Marvel’s cinematic universe stories that live across films and TV series.

But this article isn’t about the incredible tales of colorful superheroes. It’s about journalism and real-life stories.

Immersive journalism and world-building

World-building is a big component of contemporary immersive storytelling but how can we apply world-building to immersive journalism?

The Daily Bugle is a fictional newspaper of the Marvel universe

After all, journalism deals in facts, a different currency than the one traded in the realm of fiction. But journalism is also about identity and a sense of belonging. As media scholar Hossein Derakhshan pointed out in a recent article on Medium, digital subscriptions to The New York Times spiked after Trump’s election, not just because people wanted to pay for quality reporting but also because they wanted to feel part of a resistance – the membership as a badge of support for a worldview.

It’s in this sense that I here consider journalism as a matter of world-building. Reading a reportage on our favorite media outlet or watching a political talk show on our go-to TV channel is a way to use facts to build and confirm our view of the world.

Pins for The New York Times’ “Truth” campaign. The membership is here a literal badge of support

The research question that started this series of article is whether immersive journalism can represent a viable business model for the news industry. If we consider fictional storytelling, we quickly realize that what’s truly successful, also commercially, is world-building.

As master Yogurt says in the Star Wars parody Space Balls, merchandising is “where the real money from the movie is made!” And merchandising – toys, action figures, costumes, clothes, food, and so on – is a potentially unlimited resource in the ever-expanding fictional universe of a franchise like Star Wars.

Henry Jenkins calls it the “extractability principle of transmedia storytelling” and defines it as the moment “when the fan takes aspects of the story away with them as resources they deploy in the spaces of everyday life (e.g. items from the gift shop).”

Can the extractability principle become a sustainable business model for immersive journalism? In other words, can selling merchandise represent a potential source of income for a newsroom? Will journalists be in the business of selling t-shirts to their fans?

These are the questions that I’ll address in the next section.

In a galaxy far right away

You might well say that I picked the wrongest example possible. With all the journalists and media outlets that I could have referred to, I decided to pick the conspiracy theorist par excellence, Alex Jones.

Jones doesn’t even claim to be a journalist anymore. In June 2017, during a trial, his lawyers styled him as a “performance artist” active in the entertainment business. Elsewhere, I described his “news” as fiction-based and claimed that it doesn’t make sense to debunk them because it would be akin to fact-checking the physics of a superhero movie. You don’t fact-check fiction.

Alex Jones

So what can journalism learn from such an outlandish liar? Not much, but the business model behind Infowars is worth a look.

As you might know, Infowars doesn’t make money thanks to usual sources of revenue in journalism like subscriptions or ads. Jones makes a living selling stuff on the Infowars online store. And I don’t mean just t-shirts or caps for white chaps with a dubious sense of fashion. The Infowars store sells everything you might need in an imaginary world where the conspiracy theories peddled by Jones were true.

Thus, you can buy survival gears, water purification systems (the government is poisoning the water to turn citizens gay), gun “tactical” holsters, and the most lucrative product of the catalog: nutritional supplements. Jones built a snake-oil empire selling them.

A pack of strawberry-flavored caveman paleo-formula

The Infowars store sells the fantasy world imagined by Jones to his fans. Purchasing a 10-pack of strawberry-flavored “Caveman True Paleo Formula” – a mix of cartilage, bone broth, and “paleo ingredients” – the Infowars follower reinforces his identity as conspiracy theorist and his sense of belonging to the world of the story. It’s the extractability principle at its finest.

At the tail end of 2017, Harvard University’s Nieman Journalism Lab asked “some of the smartest people in journalism and digital media” to make predictions about journalism in 2018. Jamie Mottram, Gannet’s former senior director of social content, predicted that “most media brands will start selling merchandise.”

We’re now at the tail end of 2018, but I’m not aware of any particularly successful efforts in this direction. Nevertheless, I still think that merchandise can represent a valuable asset for journalism, a way to lure the reader into the world of the story and to let them spread the message on behalf of the media outlet.

If you want to continue the conversation or signal a media outlet that is betting heavily on its merchandise, please drop a line at davide.banis@gmail.com.

—

This article is the second installment in a new series that investigates whether immersive content (virtual and augmented Realities, world-building,…) could constitute a viable business model for the future of journalism.

Is Immersive Storytelling the Future of Journalism (Part I)

Is Immersive Storytelling the Future of Journalism (Part II)

Is Immersive Storytelling the Future of Journalism (Part III)