Submarine Channel

The Art Of Interactive Fiction

The Art Of Interactive Fiction

In this time of self-isolation, narrative games offer us the opportunity of exploring new worlds while interacting with fascinating characters. Technically, they’re not real people, it’s true, but it’s still better than talking to your alarm clock.

If you feel like playing video games is a too passive quarantine activity, you can start building your own interactive adventures. Thanks to a series of nifty tools, it’s less difficult than it sounds.

A good place to start your journey into the realm of narrative games is Inkle, a Cambridge-based video game developing studio founded in 2011. Not only they have a handful of very successful titles under their belt, they also built inklewriter, a no-fuss tool to create branching stories.

Screenshot from 80 Days, a narrative game by Inkle Studios (Credit: Inkle)

But maybe you first want to know more about narrative games in general or, at the opposite, you just want to start writing your next adventure. In any case, here’s a few options for you. After all, plotting your own route is a big part of the allure of interactive storytelling…

1) Err, I have no idea what you’re talking about

2) The last narrative game I played was Zork: The Great Underground Empire (1980). Tell me something about Inkle Studios

3) I just want to get started with my own story

1) And So The Adventure Begins

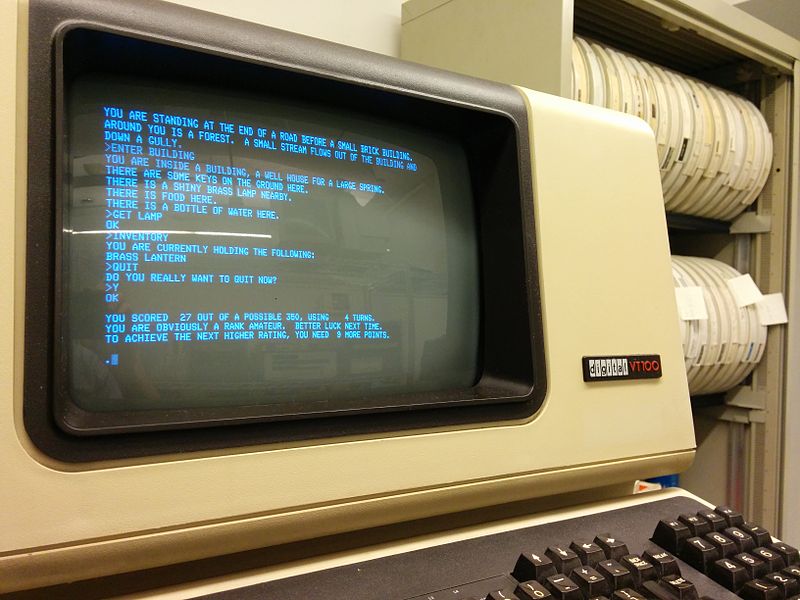

“You are standing at the end of a road before a small brick building. Around you is a forest. A small stream flows out of the building and down a gully.”

These words mark the beginning of Colossal Cave Adventure (or simply “ADVENT” as its executable file was named). In a way, they mark the beginning of the whole storytelling adventure known as interactive fiction, too.

ADVENT was originally developed by Will Crowther, a programmer who, following a divorce, wanted to find a way to connect with his two daughters. He came up with the idea of building a computer game (not exactly an obvious solution in 1976, when the game was released). Thing is, Will Crowther was not just a skilled computer programmer but also an experienced spelunker.

Indeed, as its title suggests, in Colossal Cave Adventure players explore a cave which is rumored to be filled with riches. There are no graphics, just plain text. Players can control their character by typing in simple commands. If they’re told there’s a lamp nearby, they can grab it by typing: “get lamp”.

Colossal Cave Adventure on VT100 terminal (Credit: Wikipedia/Autopilot)

ADVENT was hugely successful and inspired dozens of equally popular text adventures. Many of them were produced by Infocom, a legendary software company based in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was the time of epoch-defining titles like Zork, Deadline and the interactive fiction version of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

In his excellent documentary Get Lamp (available on YouTube), Internet archivist Jason Scott provides a glimpse into the golden age of text adventures. Those were years of limited graphics capability but boundless imagination channeled to, as it’s said in Get Lamp, “explore the power of words in an interactive context.”

Screenshot from 80 Days (Credit: Inkle)

2) Open Worlds In Your Room

Few novels express the joy of travelling as much as Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days. Now that we’re stuck at home, we can follow Phileas Fogg and his valet Passepartout in their journey across the globe thanks to 80 Days, a narrative game published by Inkle Studios in 2014.

Like in Verne’s novel, the goal is to circumnavigate the Earth in less than 80 days but, differently from the book, we can plot our own course, deciding where to go and what to do (the game’s the developers estimate that, on one complete journey, players will read approximately 2% of the game’s textual content).

The Force of text adventures is strong with games like 80 days. Similarly to Colossal Cave Adventure, Zork and Deadline, also in 80 Days, the “power of words in an interactive context” is the kernel of the game experience. And whereas, due to technical limitations, an average Infocom game contained the equivalent in words of a 30-page novella, Inkle’s adaptation of Verne’s novel is fueled by more than 750,000 words of textual content (for comparison, Tolstoy’s War and Peace consists of almost 600,000 words).

Screenshot from 80 Days (Credit: Inkle)

Textual firepower aside, the main difference between 80 Days and good ol’ text adventures is that, in the latter, you had to imagine the map of the game and, since it was too large, “you couldn’t hold it in your head and you often had to map it out yourself” while in 80 Days the map of your journey is drawn for you in an elegant decopunk style.

It’s interactive fiction at its best, a genre whose essential formula boils down to a map (in this case, the world), a timeline (80 days), an inventory (mr Fogg’s suitcases) and excellent textual content.

(Beyond 80 Days, the spirit of text adventures live in all Inkle’s games. From Heaven’s Vault—an adventure where players have, among many other things, to decipher an entire fictional ancient language—to Sorcery!—a fantasy adventure based on a series of gamebooks by Steve Jackson).

Screenshot from Heaven’s Vault (Credit: Inkle)

3) How To Write Interactive Fiction

In March, BBC’s upcoming drama Around the World in 80 Days—an international production starring David Tennant as Phileas Fogg—suspended filming due to coronavirus. The series is just one of the many productions that have been halted because of the pandemic.

An advantage of interactive fiction like Inkle’s 80 Days is that it’s easier to produce during the current crisis than live action movies and series.

If you fancy a bit of digital making, you can give it a try yourself. Inklewriter is an easy-to-use tool that can be used to write branching stories. And if you feel like taking off the training wheels, you can explore Ink, the scripting language that powers all Inkle’s games. There’s also a basic tutorial for complete beginners available.

Screenshot from Heaven’s Vault (Credit: Inkle)

In this time of hyper-realistic graphics, text adventures may seem like a relic of the past, prime examples of abandonware. Far from that, the art of “narrative at war with a crossword”—as mathematician Graham Nelson defined interactive fiction—is still very much alive thanks to production studios like Inkle.

Moreover, consider this. In Get Lamp, it’s said that the fundamental idea of text adventures was “to come up with these huge worlds where there’s so much you can see and do.” In this perspective, also graphically super-sophisticated open world games like Red Dead Redemption 2 are the spiritual descendants of Infocom adventures.

In between halted productions and people stuck at home, the pandemic is changing the world of storytelling. This is the third of a series of articles that will explore new emerging storytelling trends and how they can help us maintain (an online version of) our social life. In the end, stories are about sharing and making sense of the world we live in together.

Credit header image: Inkle