Submarine Channel

Top 5: Mindbending Dystopias in Animation

Top5's

Top 5: Mindbending Dystopias in Animation

Elections won with the aid of bots, a booming market of million-dollar supercars while more than 2 billion people live in poverty, and state leaders taunting nuclear war on social media are all things that would’ve seemed as very imaginative material for a sci-fi movie just two decades ago. But these events are part of our current reality; today’s world headlines are so fascinating and utterly terrifying, sometimes I wonder if the genres of dystopia and documentary have somehow become the same.

By Benjamin Pineros

Background art from Ghost in the Shell

Dystopia is perhaps the one genre solely dedicated to exploring those scenarios where everything just goes to shit. We could argue that animation, unconstricted from many of the rules that apply to other art forms, is the perfect medium to convey these highly inventive and morbidly irresistible visions of the future.

The first animated feature films to portray dystopian tales are probably The New Gulliver from 1935, a Soviet production that mixed stop motion, live action, and 2D animation, and Fleischer Studio’s 1939 classic Gulliver’s Travels, both adaptations of Jonathan Swift’s famous satirical work from the early 18th century.

Since then, animation, both as a technique and as a genre, has mainly been considered as an affair directed to children,—thanks Disney!—and it’s just until the 1970s that adult-oriented animated projects started to appear with relative frequency, with authors incorporating nudity, drugs, and violence into the medium.

We’ve decided to list five of the most innovative and distinctive dystopias ever told in animation; angst-ridden tales that take us from hyper-stylized versions of Paris to psychedelic far away planets.

While we acknowledge that these tales don’t make the best of date movies, we do guarantee you won’t see your smart home assistant the same way ever again.

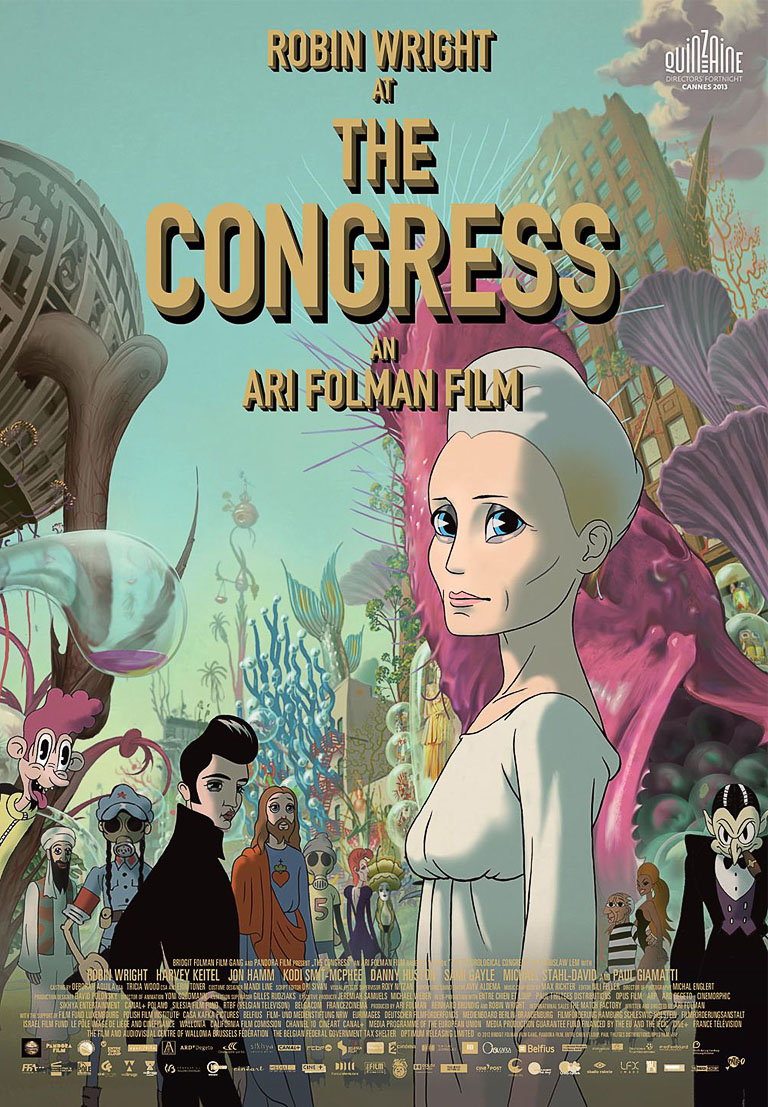

The Congress (2013)

Ari Folman’s The Congress is many things at once, and that’s both its biggest merit and its most notable flaw. Imagine an onion with so many layers, at one point it gets so complex you can’t even tell if it’s an onion anymore.

Part live-action, part animation, the movie is, in essence, a cautionary tale of capitalism gone wrong, but it doesn’t stop at that. Throw in there a multilayered love story, a very poignant commentary on identity, a scorching critique of the Hollywood studio system, lots of pop culture references and an insurgent revolution for good measure; this is one of those films that turns out to be a real a challenge to sum up when someone casually asks you, “what is it about”?

That multiplicity is precisely what makes this film so special, and also so divisive. At the time of its release, audiences and critics either hated it or liked it with equal passion.

The Congress starts off with a 45-minute live-action segment where we are introduced to actress Robin Wright playing herself. In The Congress, Wright is an aging performer who never quite fulfilled her superstar potential because of a reputation of being capricious and unreliable. As we get to know her, we learn that her career has tanked in part because her attention is mostly focused on her son Aaron, a pre-teen who suffers from Usher syndrome; a rare genetic disorder that is slowly deteriorating his sight and hearing.

Out of the blue comes an offer from the biggest player in the industry, “Miramount Studios”, which are interested in owning the rights of Robin Wright’s artistic persona. They want to scan not only her body but her gestures, movements, and performances so they can use her in as many projects as they like, just as any other digital or physical asset. (Real life studios are already doing this by the way) The deal offers a hefty sum of money, but has one caveat; she can never act again.

Despaired to see the worsening condition of her child and pressured by her manager (played brilliantly by the great Harvey Keitel) Wright accepts the deal in a 20-year contract.

It’s at this point where the film splinters off both stylistically and thematically, moving from a grounded live-action universe into a psychedelic, wacky toon world reminiscent of the Max Fleischer cartoons of the 1930s and loosely inspired in Stanisław Lem’s classic sci-fi novel from 1971 The Futurological Congress.

The movie fast-forwards two decades into the future when the contract is close to expiring. The studio is interested in renewing their agreement and invites Robin to speak at an annual congress where they unveil their latest productions. What makes the soiree special is that it’s held not in any physical venue, but in a reality that only exists in every assistant’s mind.

It turns out, in this hypothetical future pharmaceutical companies have made an unlikely alliance with Hollywood studios to develop the new frontier in entertainment; a drug-induced state where people escape from reality to adopt any shape they want and carry out their fantasies in a universe unhindered by any sense of morals, law or even physics.

Israeli-born director Ari Folman made a brave move when he departed from the documentary approach that earned him so much praise with Waltz with Bashir, to plunge himself into this expensive, risky and convoluted affair.

It feels like this is Folman’s ambitious attempt to make “a mother of all movies”, that film that manages to be relevant and prescient, heartfelt and intellectual. And well, he did throw everything in there, kitchen sink and golf clubs included. Yet, not having a restraint is precisely what dilutes the impact of the film and makes it so discordant.

Nevertheless, it still stands as a thought-provoking, masterful piece of cinema that raked up ten awards in festivals all over the world, including best European Animated Feature Film in 2013.

If you’re in the mood for a trippy, poetic ride with fantastic acting, look no further.

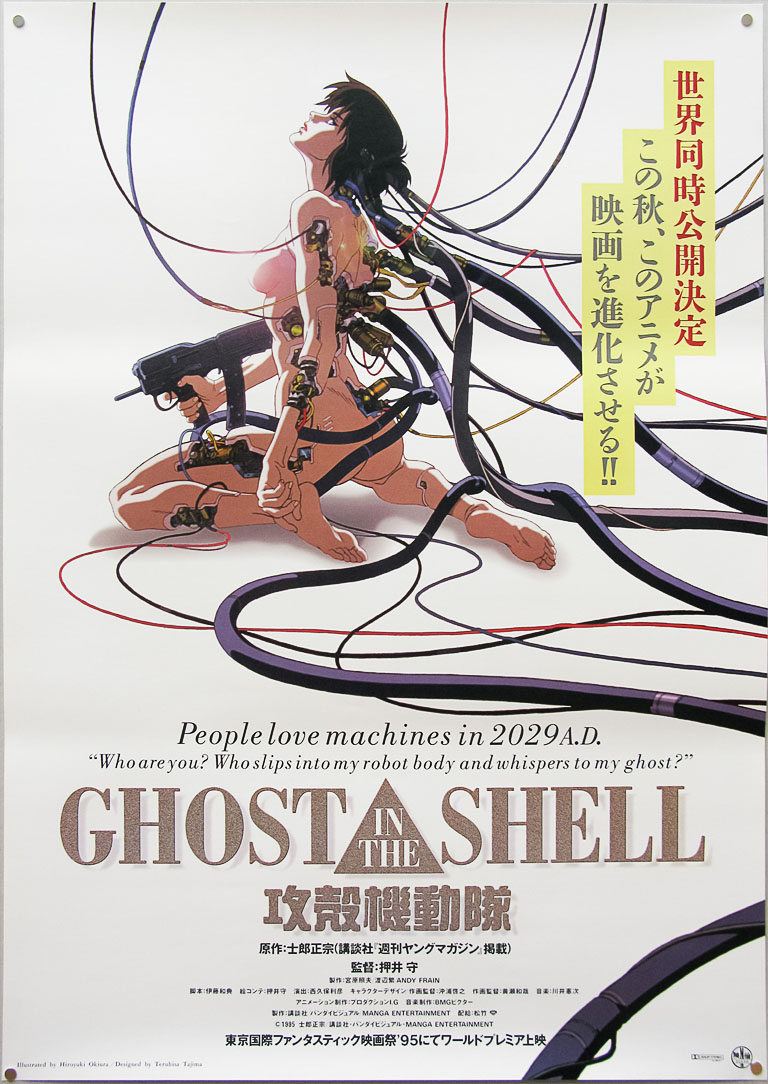

Ghost in the Shell (1995)

Flashy action scenes? Check! Political intrigue? Check! A deep philosophical exploration of the meaning of life? Hmm, yeah. Check! Nudity? Hell, that too. Check! If there is a film out there that could be described as “perfect”—if such a concept exists anyway,—this is as close as it gets.

The story takes place in the near future, in a world where people have artificially controlled metabolisms, computer-enhanced brains, and cybernetic bodies. Criminals are able to hack into minds and synthetic beings seek political asylum. Ghost in the Shell is not only a thought-provoking dystopian vision of the future but has a place among the pantheon of titles that helped define the cyberpunk subgenre, along with William Gibson’s Neuromancer, Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira and Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner.

The film follows the exploits of “Section 9”, a special-operations task-force assembled from former military and police agents to combat cyber-criminals and terrorists. Yet, the police procedural aspect is just a Trojan horse that carries a much deeper, philosophical inquiry: What does it mean to be human?

Major Motoko Kusanagi is one of the top agents of “Section 9”, a cybernetic organism composed of a human brain enclosed in a fully synthetic body. She was designed to be a highly efficient and lethal weapon in service of the government, but under the stoic and resolved facade of a loyal enforcer, she hides a pensive, troubled character. Not only does she question the real motivations of her superiors, but constantly wonders about her very own existence.

If that reminiscence of your first kiss, if that image of your spouse holding your baby for the very first time, along with all the rest of your memories, were at the end just a pile of data, would that make you any less human?

The very title, “Ghost in the shell” refers to the concept of consciousness, or soul, that is “trapped” in our body. It’s a premise that alludes to the thought experiment known as “brain in a vat”, a question that has been making people scratch their heads as early as Hindi tradition and has been tackled in one way or another by many philosophers from Plato to Descartes.

What if we could remove a person’s brain from their body, and somehow trap it in some kind of apparatus that provided it with the same electrical impulses that it receives naturally. In theory, the brain would continue to create a “life” and have normal conscious experiences as any other normal person with their brain in place. Furthermore, that disembodied brain won’t have any means to realize what its experiencing is a simulation and not the real thing.

This scenario inevitably ignites a flurry of questions. What is real? What is that thing that defines us as human? Our experiences, or our corporality? And here’s a fun one… how can we be so sure that what we’re living right now is real and not a simulation?

Ghost in the Shell not only provides plenty of food for thought but as a whole, is a brilliantly executed piece of cinema.

Director Mamoru Oshii chooses here to approach the mise-en-scene as a live-action project, limiting the camera’s movements as if he was constrained by tripods, dollies, and cranes. The film is stylistically closer to something from Yasujirō Ozu or Jacques Tati than to a traditional anime, especially when he opts for wide, static shots that allow the events to unfold uninterrupted in front of the “lens”, embedding the film with a contemplative, eerie tone.

The backgrounds are a work of art in itself, each frame a painting that breathtakingly depicts colorful, battered shanty towns coexisting with mammoth high tech skyscrapers and futuristic vehicles.

A world where people enhance their bodies with robotic parts, and everybody is connected to the net is a premise that sounds quite natural today, which makes it easy to forget that the universe of Ghost in The Shell was created twenty years ago in the original manga by Masamune Shirow.

Influential, relevant and brilliantly executed, this is one of those works where everything just clicks. If you’re in the mood for sexy robots that go scuba diving in their free time, recite existential poetry and kick some serious ass, then this is the one for you.

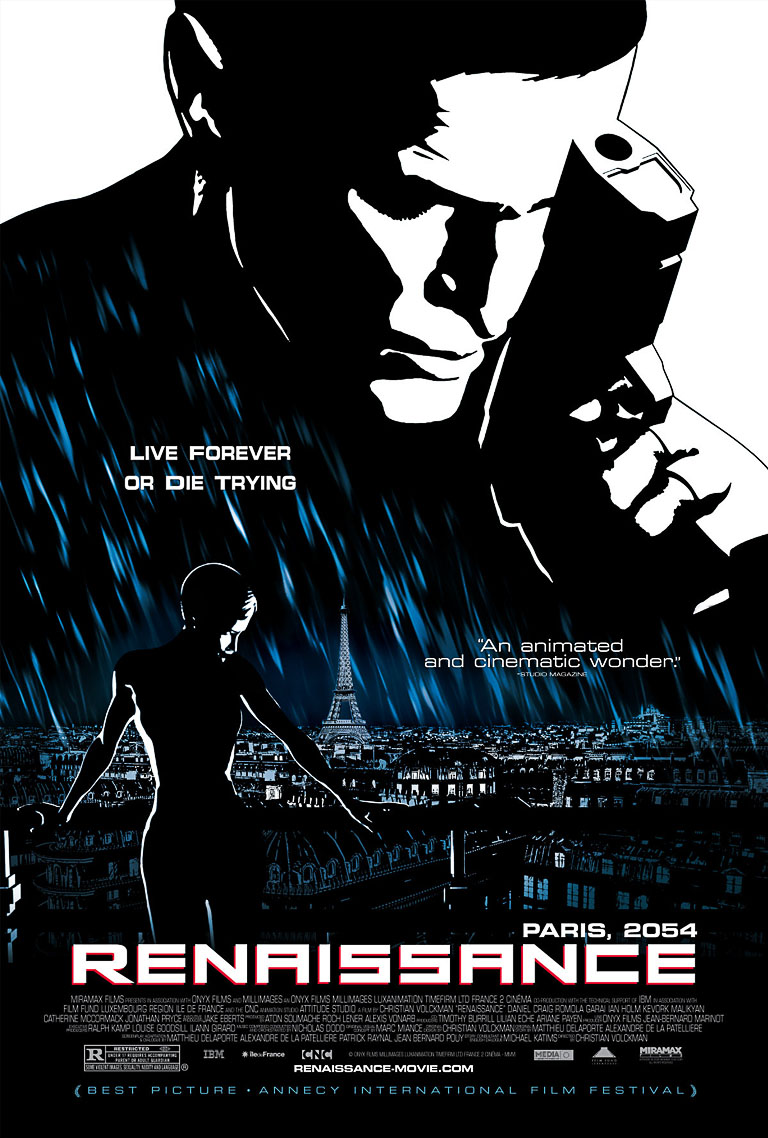

Renaissance (2006)

Paris in 2054 is an overpopulated, crime-plagued city where people resort to drugs, digital entertainment, and excessive consumerism to escape from the dullness of 9 to 5 work.

Demographic explosion forces the metropolis to grow upwards, with towering buildings built on top of other buildings giving the cityscape the resemblance of a mammoth termite mound made out of glass, concrete, and steel.

As far as dystopias go, Renaissance doesn’t really venture too far from our current state of things; worldbuilding isn’t something truly groundbreaking or particularly special as it chooses to depict a futuristic, yet familiar universe that hits a bit too close to home.

However, what does make of this one of the most underrated movies of the last two decades is an utterly unique stylistic approach that I’d argue had ever been done before, or since.

Directed by painter and author Christian Volckman, Renaissance is part of a wave of high profile films in the early aughts—Attack of the Clones (2002), Dogville (2003), Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004), Sin City (2005)—that pioneered in the adoption of digital filmmaking tools and experimented with the aesthetic possibilities of what was back then a brand new medium.

The crew of Renaissance embraced the use of motion capture technology and virtual environments years before much more popular films like The Polar Express and Sin City. In a rented warehouse in Luxemburg, the filmmakers spent nine weeks shooting the movie and capturing the actors’ performances to feed the animation team with enough data to create this utterly distinctive vision of Paris.

The whole project took in total over six years to make on an $18 million budget collected from various sources that included Onyx, Canal Plus, France 2, Disney and Miramax. Just to put that number into perspective, Blue Sky’s Ice Age: The Meltdown from the same year had a budget of around $80 million.

So, what about the story? Well, in a nutshell, Renaissance is an old school whodunnit with a twist. Under all the technology and heavy stylization, the film is at its heart a classic crime mystery in the best tradition of the French masters of the genre, like Daphne du Maurier, Louis Malle or the duo Boileau/Narcejac.

Avalon is a mega-corporation that develops beauty and health products, a conglomerate so powerful you can’t walk two blocks without seeing one of their ads. Imagine a fusion of Johnson & Johnson, Coca-Cola, and Apple.

Ilona Tasuiev is a young scientist developing for them a secret anti-aging project, but one good day she ends up being kidnapped in strange circumstances. Hard-boiled cop Barthélémy Karas is assigned to solve a convoluted case in which nothing is what it seems, and soon, he will find out it’s not only the scientist’s life which is at stake, but the fate of the whole human race.

Sure, character development is thin, and relationships feel rushed and an even a bit cheeky. But the huge merit of Renaissance is to achieve an incredibly singular vision of the future that hasn’t been done before it. Simply put, there is no other film out there like this.

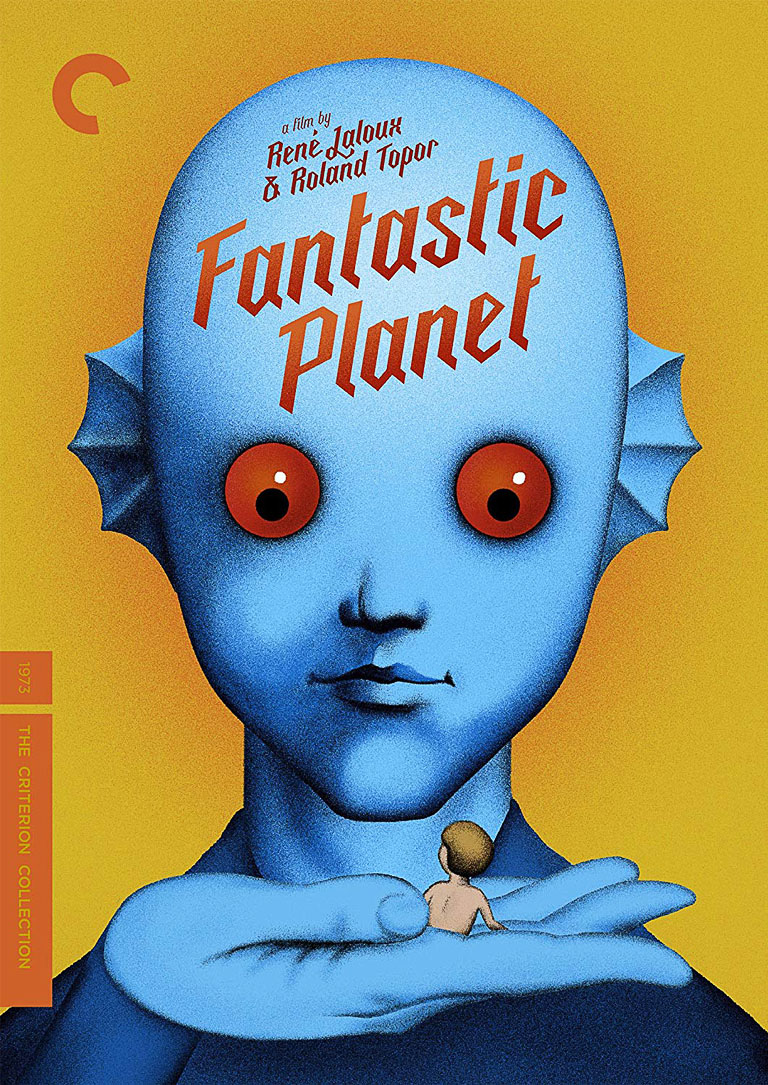

Fantastic Planet (1973)

Society has achieved a state of peace and prosperity where there is little trace of social classes. Democracy has proven to be the most efficient system to keep the balance of power and discrepancies are solved through arduous but civil argumentation.

Thanks to incredible technological progress, basic needs are satisfied and citizens have the leeway to spend the majority of their time fostering their intellect and spiritual wellbeing.

Wait, this doesn’t sound like a dystopia at all you’d say. And well, yeah, this wouldn’t be a dystopia, if it wasn’t because what I’m describing is not Earth, but planet “Ygam” and their inhabitants, the “Draags” have brutally enslaved the human race, treating us like a pest akin to rats, or in the best of cases, like pets.

The Draags dress us up in the most ridiculous outfits, put us to fight against each other for their amusement, and discipline us when they seem fit.

Fantastic Planet inverts our relationship with animals and extrapolates it to this technologically advanced planet ruled by a race of giant blue bipeds. They use humans for their enjoyment in ways we feel shocking and perverse at first until we realize that’s exactly what we’ve been doing to animals since time immemorial.

An international co-production between France and Czechoslovakia, the film was a huge critical hit on its release in 1973, snatching the Grand Prix special jury prize at that year’s Cannes Film Festival and a myriad of other accolades all over the world. Curiously, its prominence faded shortly afterward and “La Planète Sauvage” was largely forgotten for almost thirty years until it was re-released in DVD in the early aughts, allowing it to be discovered by a new generation that fell captivated by its trippiness and turned it into a cult hit. The film has gained such a renewed interest that in 2016, Rolling Stone ranked it as the 36th greatest animated movie ever made.

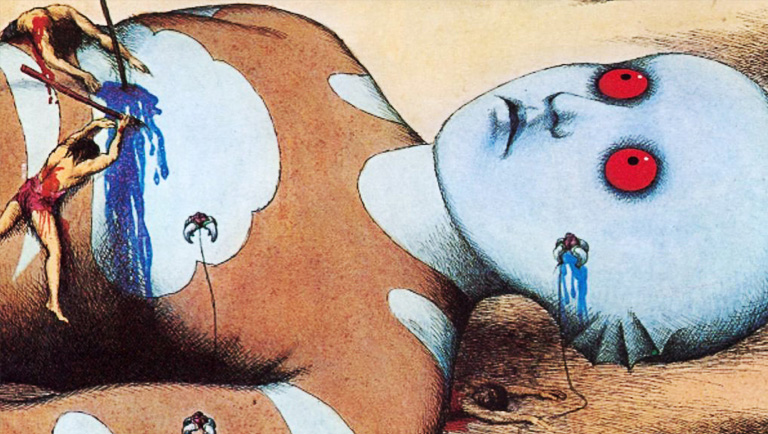

To render this incisive allegory, director René Laloux resorted to the cutout animation technique, which is a form of stop-motion animation in which every element in the frame—characters, backgrounds, props—is not a three-dimensional figure or a sculpt, but a “cut out” of a drawing or a photograph. Each layer can be made from basically any material, with paper, cardboard and stiff fabric being the most used.

Cutout animation is probably the very first animated technique to appear in cinema, and although today computers have mostly replaced the process of physically cutting each element, the technique is still used, most famously in the popular comedy South Park.

Disquieting, psychedelic and vastly imaginative, Fantastic Planet depicts the Draags as a highly developed and intellectually driven civilization. Yet they are so self-assured of their superiority, they fail to recognize “inferior” species as thinking beings with their very own intelligence and emotions. Despite the sophistication of their culture, the Draags end up being as savage, or even more, than those creatures they consider as vermin.

Rings a bell?

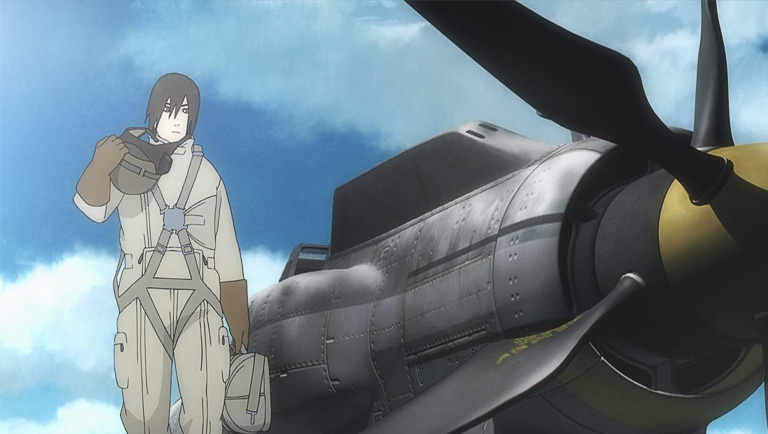

The Sky Crawlers (2008)

Based on Hiroshi Mori’s highly successful novel of the same name, the movie focuses on the lives of a group of teenage fighter pilots who blast off into the skies every single day to battle against a mysterious and powerful enemy.

Events can be a bit confusing at first, as the film doesn’t spell out in one go the whole scope of the story. It doesn’t set up the conflict nor the character’s motivations from the outset, instead, it opts to throw one by one, little pieces of the puzzle for the audience to put together.

The first time I ever watched The Sky Crawlers was one night after a long day at work, in one of those moments when you know all your energy reserves have been depleted, every single hair on your head hurts, and the only thing you really want is to disappear into the mattress.

After 10 minutes it was impossible for me to take my eyes off the screen.

The movie is set in a hypothetical future where the world has achieved peace, yet happenings are very similar to our days. There’s political tensions, dangerous chemicals found in crops and ferocious international trade disputes.

Interestingly, worldbuilding is never spelled out directly, and there’s no obvious signs or grand establishing shots of megacities to illustrate the state of affairs. Context is executed throughout the headlines of newspapers or shots of TV screens covering the news, and it’s only through these subtle hints that you get to know what’s happening in the world of The Sky Crawlers.

In this dystopian society, although countries have achieved peace, warfare still exists, but in a very different incarnation from what we’re used to. Blood is spilled not in the name of ideologies, religion or nationality, but in the name of entertainment and collective sanity.

The world has found that conflict is an inherent necessity in human society, a nefarious affair that gives a sense of tension and reality essential for civilization to hold together.

The film argues that it’s only through the horrors of war that we are able to grasp the meaning of peace and value it. Reading the stats of war casualties in textbooks is not enough, we need to know that someone, somewhere is being killed or is killing in the name of an ideal.

As radical as this premise sounds, it reminds me of a weird phenomenon that’s appearing in our current times. Most of the people who went through the atrocities of WWI and WWII have gone, and the memory of these Earth-shattering events is slowly fading.

In the absence of tangible reminders of those nightmarish times, we’re seeing among younger generations the rebirth of ideologies that from a platform of hate and intolerance seem eager to push society into a brand new conflict, ignoring the lessons from the past, and lightheartedly taking warfare as if it was a videogame.

In The Sky Crawlers, these staged wars are held not between countries, but between private corporations that breed genetically modified children called “kildren”; expendable clones whose sole purpose is to fight.

The whole movie is structured around a series of spectacular dog fights interspersed with sequences of deep character development and existential pondering, which makes of The Sky Crawlers an appealing romp both to lovers of action-packed anime as well as those who prefer their stories with a healthy dose of existential angst.

If there is such a thing as a film capable of uniting the fans of Dragon Ball and Ingmar Bergman under the same turf, well, this might be it.

Not only is the film an exploration of military conflict in society, but a reflection of identity and fate. As these “kildren” grow aware of the cruel purpose behind their existence, an inevitable question starts to brew in their minds. Do they have a choice? Can their free will revert the purpose for what they were born?

“Even if it’s always the same road we walk, we can still step onto different places. Even if it’s always the same road we walk, the scenery is not the same.” muses at one point one of the main characters.

Another critically acclaimed work from Ghost in the Shell director Mamoru Oshii, this mix of 3D and 2D animation was one of the absolute festival darlings of 2008, winning accolades at the Toronto film festival, Sitges, Mainichi and Venice, plus a heap of nominations all around the globe.

The Sky Crawlers is one of those works that can either go over your head or become one of your favorite films of all time.

Benjamin is a writer, self-taught filmmaker, 3D artist and cook extraordinaire. He has worked in feature animated films, indie video games and is currently a contributor to Australian digital publishing company Conversant Media. In love with all good sounds from Bach to David Bowie, he writes first drafts on paper, hates smartphones and wants to learn to play the guitar someday. For years, Benjamin has worked in his spare time on his personal project “Servicios Públicos” a sci-fi dystopia about tyrant states, overpopulated Latin American cities and some damn awesome robots. Find him on Twitter @iampineros