Submarine Channel

Clayton Patterson Interview

Clayton Patterson Interview

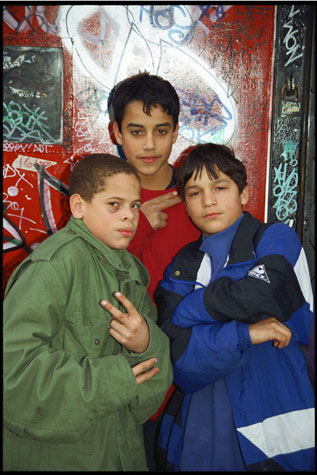

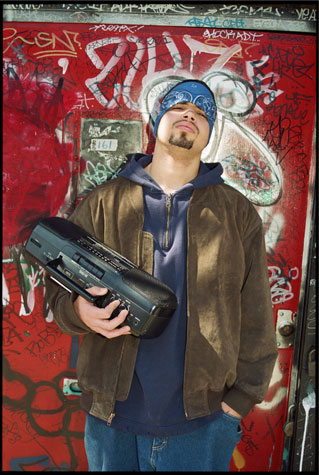

Since 1979, renegade photographer Clayton Patterson has dedicated his life to capturing the mutating subcultures of New York’s Lower East Side. Recently released documentary Captured, weaves together his unique footage – from the gangster kids who brought us graffiti, to CBGBs, the legendary home of punk, to the Starbucks and Ed Hardy homogeny that now characterizes the area, Mr Patterson has been the arbiter of the area’s cultural heritage. Captured is now available on DVD and will be screened at various underground venues throughout Europe this Spring and Summer. We enjoyed an inspirational phone conversation with Mr Patterson as he introduced us to some of his fascinating insights into the rise and fall of contemporary culture. Some highlights:

Can you tell us how you started out filming on the Lower East Side?

I came to New York from Western Canada in the late 1970s to be an artist, to make my mark on the world. At that time, my girlfriend and I didn’t need a steady job. You could do so many things with so little money, it just had that vibe, that energy. I started off taking still photos and didn’t actually start shooting video until 1986, when I was introduced to the film camera by the father of Ben Solomon, who co-directed Captured.

What do you think was special particularly about the Lower East Side that fostered this level of diversity, individual expression and creativity?

A combination of cheap rents, and the presence of many poor immigrants. Large pockets of people like Jews and Puerto Ricans were struggling to get out of the ghetto and expand. Coffeeshops were buzzing with immigrants talking about new ideas, sharing energy and enthusiasm. And the relics of previous populations who had already moved on, the Ukrainians and Polish with their kilbasa and perogi, fostered this spirit of endless possibility and equality among pockets of poor people.

All that has now been lost, those layers that were left here over 150 years and all their riches, have been simply wiped out.

Was there a defining moment that solidified your status as the Lower East Side’s official archivist?

The thing that made me famous was when I shot a video tape of 3 hours and 33 minutes during a police riot in Tompkins Square Park in ‘88. Larry Davis shot 6 cops with a gun, and I got 6 cops indighted, shooting them with my video camera… That put me on the map. CNN, Oprah, Geraldo, the New York Times – they all invited me for interviews and I was kicked me into the world of street politics.

Coming from an obscure situation and a poor family it was amazing that you could have an influence on society – that was really exciting for me.

What led to the creative downturn and standardization of the area?

Back in the day, all the genius of New York was connected to the cheap rents; the 99 cent breakfasts would keep artists like Lou Reed or Jimi Hendrix going all day. Now an apartment on Ludlow costs three grand a month. How can creativity flourish with those prices? Before you could work two nights at the Bowery and be covered. Now, the 99 cent breakfast has become 12 dollar brunch.

We also always thought when we got rid of the drugs it would be a great neighborhood. But the reality was, when we got rid of the drugs, the money came in and that killed the spirit. It turned New York into another “bla bla” city. Building up people like Paris Hilton, Britney but not bringing up the new Charlie Parkers, Rothkos, Jackson Pollocks – they can’t be here anymore. Neither can Clayton Patterson. It’s no longer possible to be poor and work your way up. Effectively the American Dream has been washed away.

CBGBs was like our cathedral, our Notre Dame. We’ve lost our cathedral, and now you can go in and buy CBGB “Home of Punk” t-shirts by John Varvatos there for ridiculous prices. Varvatos has co-opted punk and sells the t-shirts for $400 a piece!

Where, if anywhere, do you think would be the new Lower East Side of today?

If I was 27 now, I think I would go to China –everything is Chinese now, that’s where the juices are flowing.

Is there still hope for grass-roots activism and underground creative movements to flourish today?

Definitely! A 21st century model based on digital tools, internet and so on, has real potential – especially among youth.

The same way graffiti went global, there’s now that same feeling of global inter-connectivity, passing ideas around outside of establishment. If we stay connected and exchange our energy we can do things on a global scale. As long as the youth can keep those goals in mind, do what they need to do and share it. In the past it was all narcissism, now people are sharing with mass global exchanges, and this has massive potential for generating change.