Submarine Channel

Tips For Making Web Projects Future Proof

Top5's

Tips For Making Web Projects Future Proof

This will come as no surprise to anyone: the Internet is about the least steady medium in existence. Browsers update. External sources die. APIs are blocked. Highly dynamic kinds of content are especially at risk, as their online environment is ever-changing. The kind of works Submarine Channel features need continuous maintenance to keep working. Yet who has the time and resources to feverishly update every single website for years, decades even? Does a way to preserve groundbreaking productions for future generations even exist?

More and more archives and libraries worldwide have taken up the task of preserving websites. They are organized in the International Internet Preservation Consortium (IIPC). Their goal? Making sure future generations will be able to understand the development of the Internet in our day. These institutions are especially challenged by more dynamic web pages created by artists. The possibilities of digital network technology are used in creative and unexpected ways. The standard tools and workflows especially struggle with technologies like Flash and JavaScript.

Perhaps not every project needs to be preserved. But already some iconic and innovative projects are rendered useless. Which, as cultural objects, tell an important story about media, technology and society. So is there anything that developers of web projects can do to help archives to do their work better? Jesse de Vos, researcher at the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, offers five suggestions.

1. Before you start: consider the end

A gap often exists between the publication of material and the adoption into an archival collection. For a book or physical object this doesn’t present us with a real problem. The ephemerality of websites however presents us with a challenge, even just a few years after publication.

It would help a great deal if at the start of a new project, makers would consider long-term availability and archivability of the project. Makers could seek cooperation with regional, national or thematic archives that might be interested in adopting the project in their webarchive.

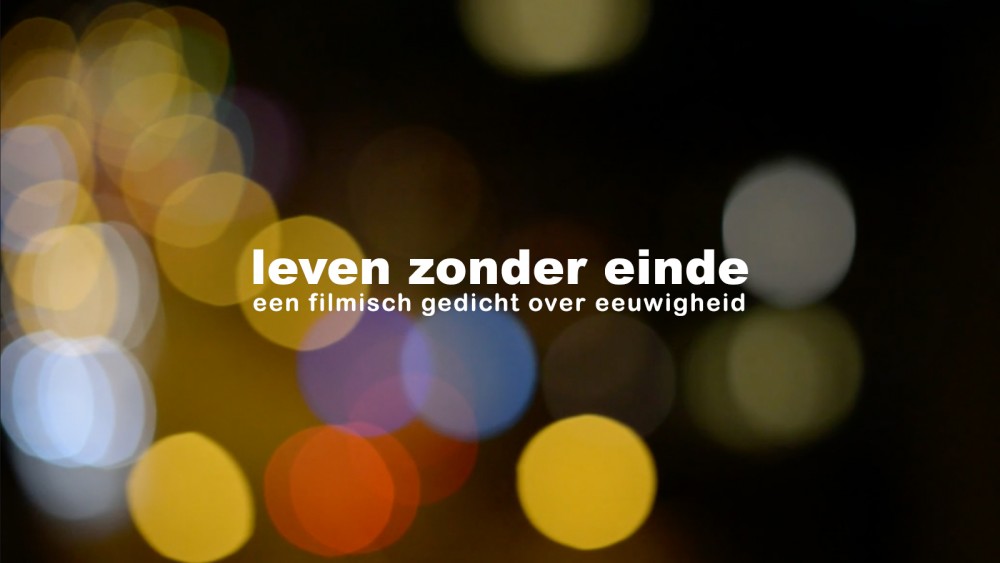

Vanesa Abajo Perez is a filmmaker currently working on a project called Life without End. Together with poet Maud Vanhauwaert she will process the input of people who suffer a life-threatening illness in the form of filmic poems. She approached the archive that I work for, the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, early on in her process. Perez: “Life without End will eternalize people with a fatal illness in their own surroundings. As I considered the form, I intuitively knew that archiving the project would be very important, not just as a technological necessity, but an artistic one.” Together with the filmmaker, we discussed the possibilities for future preservation of the project. We will make sure that the materials produced comply with standards the archive can deal with as much as possible.

2. What’s a WARC?

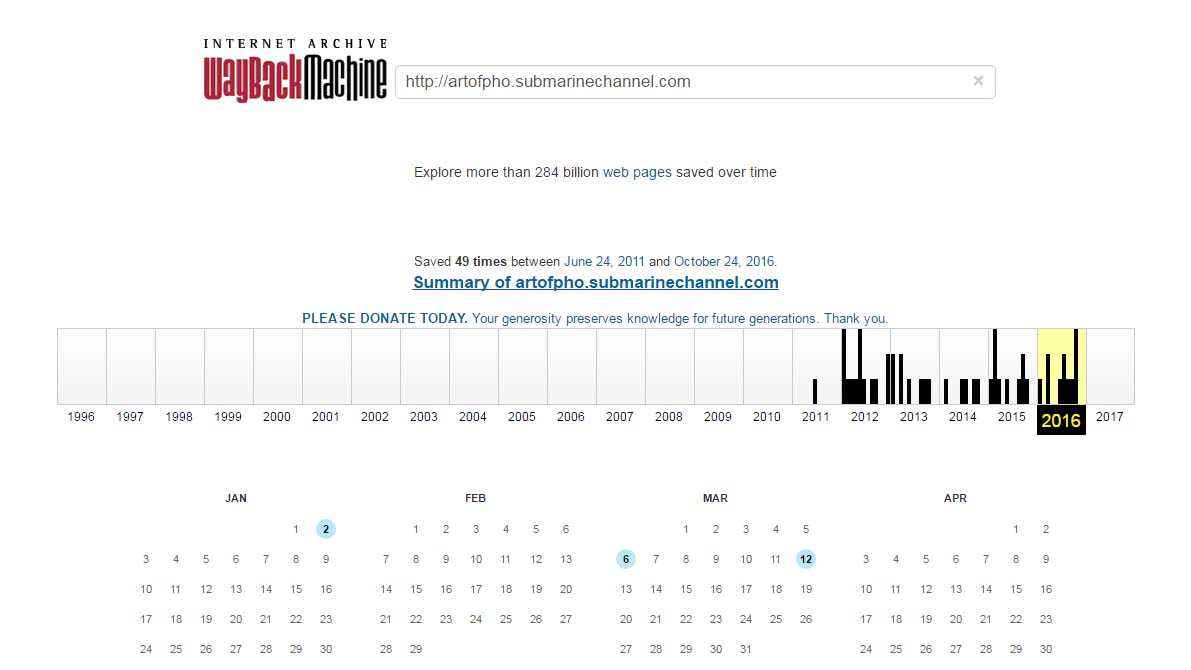

There is a standard workflow that most webarchives use. A webcrawler, most likely Heritrix, will crawl a website-URL (make sure robot.txt doesn’t limit the crawler!). It will then convert the crawled material into a so called WARC file: an aggregate archive file that contains the html, images, etc. and comes with basic metadata. These WARC files can then be displayed in something like the Open Wayback Machine. The largest webarchive in the world, The Internet Archive, has collected over 280 billion (!) web pages in this way. It works well for text and image-heavy websites. It struggles though with embedded media, dynamic webcontent, complex link-structures and of course external dependencies. More recently tools are being developed that are better at crawling this type of content, the most accessible of which is Webrecorder.io. It requires some manual labour but already shows to be quite successful with some websites, so it is worth checking out.

3. Play by the rules where you can

The flexibility of web technology creates a plethora of possibilities for artists and storytellers which by all means should be used. No archive is after limiting the creativity of makers. Where possible however, complying to a few simple rules can increase the likelihood of your project surviving the ravages of time.

- Apply standards

Use site maps, use stable URLs, use open formats, provide meaningful titles and web addresses, to name just a few. There is a more extensive extensive checklist composed by the Library of Congress that might be helpful. To make things a little simpler a proof of concept tool was developed that scans your website for issues that might limit the options for crawling its content. It will give a general idea of your websites’ archivability and allow you to make adjustments where possible. - Think about dependencies

Realize that every external source or database used that fundamentally changes the behaviour of your web project will make long-term accessibility and archivability that much harder. If there are ways to accomplish the same effect without using external sources, you might want to consider it. - Intellectual Property

For most archives saving websites without being allowed to make them available to a wide audience is at odds with their mission as publicly funded institutions. Make sure you can provide clarity about who owns what. It helps a great deal in reaching agreements with archives about the exploitation of the project once archived.

4. Document the documentary

So you’ve created your interactive documentary, carefully considering the interactive elements as a way to engage, disrupt or inspire your audience. In some instances we have to accept that the standard tools don’t work (yet?) for these dynamic parts. Where funds are limited non-standardized, labour intensive approaches might also not be feasible.

An easy way to let your project live on in a different form is by documenting it. Even though we have to accept a loss – the loss of the experience of interacting with the project – not all is lost. Documenting the project with a simple screen capture of someone navigating the project is a good start. But how about adding a layer of information by creating a walk-through with makers-commentary? Or how about having a user record his or her experience in “Let’s Play-video”-style? The resulting videos are much easier to preserve for the long-term and give a good idea of the form and content of the production.

5. Same ingredients, different dish

If possible, consider keeping the source files separately (text, photographs, video, etc.) that make up your project. New versions and interpretations of the original web project can then be created for a different audience, a new technology, a different context. Sometimes this is necessary to convey the intended message. Sometimes simply because older versions stop functioning.

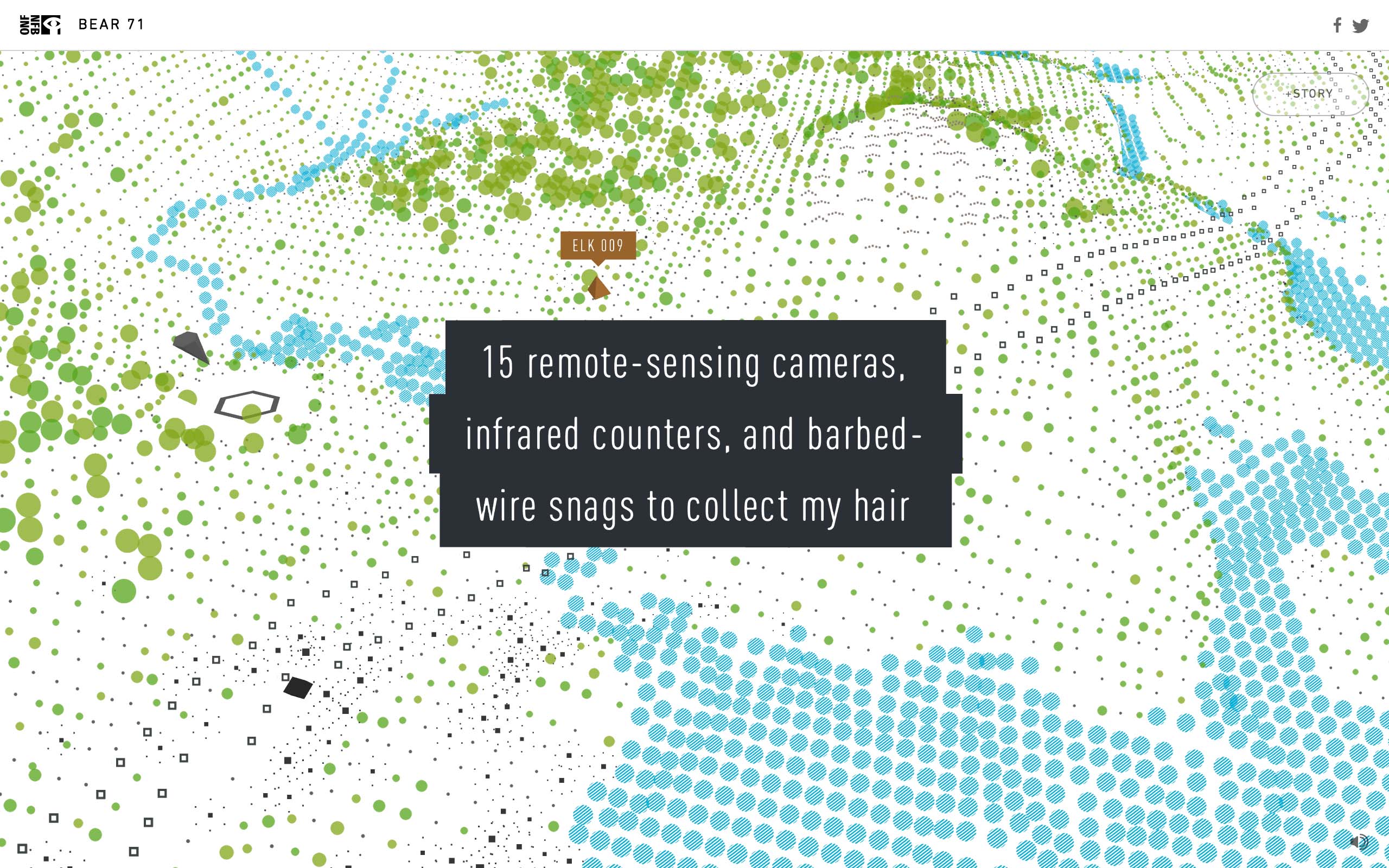

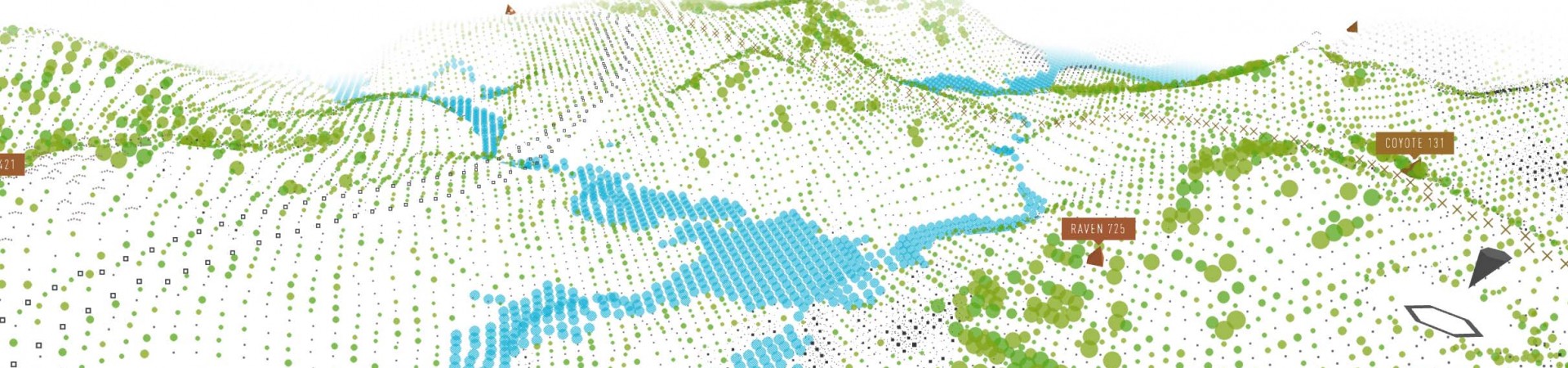

The iconic interactive documentary Bear 71 (NFB, 2011) was originally produced in Flash for a web browser. But to celebrate IDFA Doclab’s tenth year anniversary IDFA and the Netherlands institute for Sound and Vision co-commissioned the original creators of the project to reimagine the experience in Virtual Reality. Using the same content and the same story the documentary is now more immersive, and up-to-date with recent technology for at least some years to come.

Additional watching and reading:

Update or Die: Future Proofing Emerging Digital Documentary

This one-day conference about interactive documentary preservation, curated by MIT Open Documentary Lab and Phi Centre, in collaboration with IDFA DocLab took place on May 5, 2017.

Jesse is a researcher at the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision, a cultural archive and museum. He has been been looking at ways of improving the organisation’s web archiving activities and solutions for the preservation of dynamic web content. Twitter: @85jesse

Two creators of Radarsoft comment on their video game in a Let’s Play-video produced by the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision.

Two creators of Radarsoft comment on their video game in a Let’s Play-video produced by the Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision.